by Sue Ann Kendall

We had our first online Chapter Meeting last week, and while it wasn’t totally hitch-free, it went well enough that everyone enjoyed the advanced training and meeting, I think. We had nearly 30 attendees, which is a reasonable number for our chapter at any time!

Our speakers were Dr. Paul Crump (Herpetologist) and Dr. Elizabeth Bates (Conservation Initiatives Specialist) from Texas Parks and Wildlife. They graciously provided the WebEx link for the meeting, since we didn’t have our shiny new Zoom account yet (we do now, thanks to Mike Conner).

Conservation of Rare Species

The first part of the session was about programs that exist in the US and Texas to protect endangered and rare species. It gets pretty complicated, since species can be listed as being of greatest conservation need at the federal level, state level, or both levels.

One thing that Dr. Bates stressed was the need to be pro-active about protecting these plants and animals. She encouraged landowners to take advantage of programs, such as Safe Harbor Agreements, to protect and enhance dwindling habitats. Something easy and rewarding that any of us can do is log sightings of rare and endangered species in iNaturalist. That way, researchers can see if they are increasing, decreasing, or staying the same.

You can find more information on this topic at the Texas Parks and Wildlife department site.

The Houston Toad

For the second part of the presentation, Dr. Crump, who has worked with the Houston toad (Bufo houstonensis) for many years, provided an example of the work that’s been done to protect and expand the range of this Texas native. The Houston toad took quite a hit when one of its primary sanctuaries, the Lost Pines area near Bastrop, burned so badly.

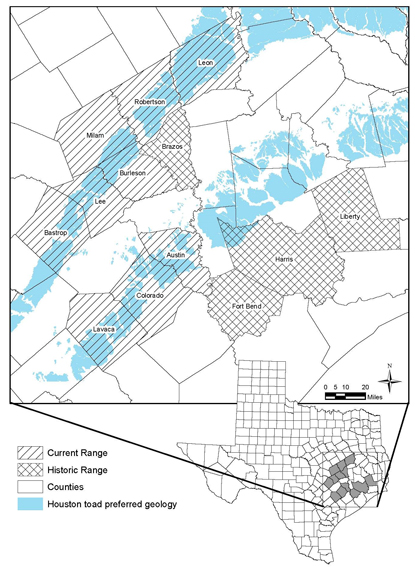

Crump shared maps of where the toad used to be found and its current range (which does NOT include Houston), which includes parts of Milam County. Later he did say that only five have been found here. The Houston toad is the only toad that’s found only in Texas, by the way. There are eight other toads found in this state, but the one we usually see is the Gulf coast toad.

We learned that these toads like to breed in bodies of water that aren’t permanent, perhaps because they are less likely to hold fish and turtles that would eat their eggs and developing tadpoles. They’ve bred in many ponds and such, though. Their most sensitve time is right after they crawl out of the water, because they need leaf litter to hide in, and they are easy to squish. Eventually they head out to sandy soil where they can hide by burying themselves.

The smaller males tend to live a year, while females take two years to mature, due to their size. Most only breed once. We are lucky that there has been some success breeding them in captivity and setting the little ones in ponds (it’s way too expensive to feed them to maturity; it requires mega-large amounts of crickets.

It’s easy to tell a Houston toad from a Gulf coast toad if you know where to look. Houston toads have more freckles on their bellies and are quite green where their neck balloons out while they call. Gulf coast toads have a large cranial ridge that the Houston toad lacks, too. Their calls are really different, with the Houston toad being much higher in pitch. Basically, you’ve probably never seen or heard one.

But don’t let that stop you from looking, because the researchers need data on where they have been sighted! Crump and his colleagues would also love to have more participants in the Houston Toad Safe Harbor Agreement, which is a way for landowners to agree to protect their toad habitat.

If this doesn’t satisfy your curiosity, the slide deck from Crump’s presentation is available on our website, and there’s great information on the TPWD website as well.