by Michelle Lopez

The first time I saw it, I knew immediately it wasn’t a Northern Cardinal.

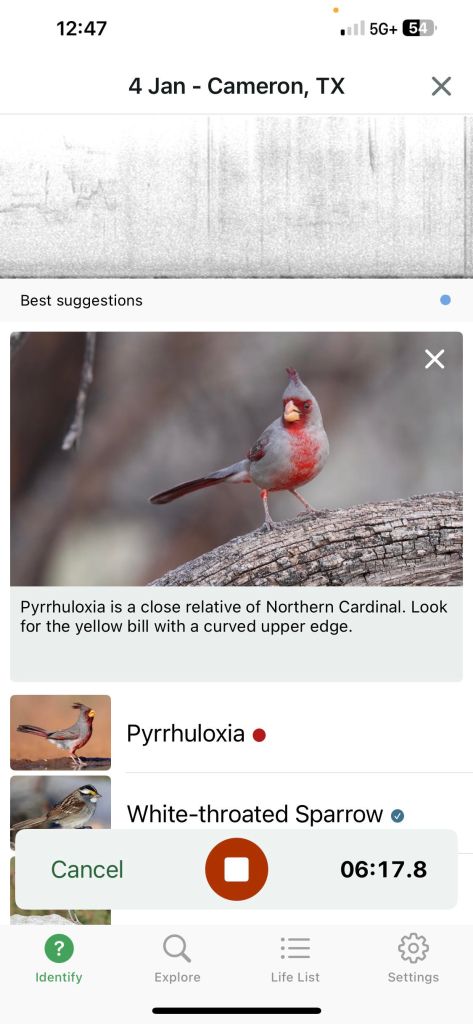

At a glance, it had that familiar cardinal shape, but something was different—more gray overall, with muted red highlights and none of the bold black around the bill. At the time, I didn’t know exactly what to look for, only that my eyes were telling me this was something else.

Later, as I learned more about the Pyrrhuloxia, one detail stood out: the beak. Unlike a cardinal’s thick, conical bill, the Pyrrhuloxia has a distinctly curved, almost parrot-like yellow beak. Once I knew that, everything clicked.

Not long after, I saw the bird again near the pond at Twisted Creek Ranch. This time, I was ready. The curved beak was unmistakable. As if on cue, the Merlin Bird ID app also picked up its call, confirming what I already felt deep down—I hadn’t been mistaken.

The Pyrrhuloxia, sometimes called the “Desert Cardinal,” is far less common in Central Texas than its bright red cousin. Seeing one is a reminder of why slowing down and paying attention matters. Sometimes it’s not about bold colors, but subtle differences—the shape of a beak, a softer call, or that quiet inner nudge that says, this bird is special.

Moments like this are exactly why I love living and observing nature here. Every season brings the possibility of something unexpected, and every observation deepens my connection to this land.

Keep watching. Keep listening. Nature always has more to reveal.

Did You Know?

- The Pyrrhuloxia’s curved beak is specially adapted for cracking hard seeds, especially those found in arid and semi-arid landscapes.

- Though often called the “Desert Cardinal,” Pyrrhuloxias are actually a separate species and lack the cardinal’s bold black facial mask.

- Females are even more subtle than males, appearing mostly gray with faint red accents, making them easy to overlook.

- Pyrrhuloxias are most commonly found in thorny brush, mesquite, and scrub habitats, which makes sightings in Central Texas especially exciting.

- Their song is softer and less musical than a Northern Cardinal’s—another reason apps like Merlin can be helpful for confirmation.