by Lisa Milewski

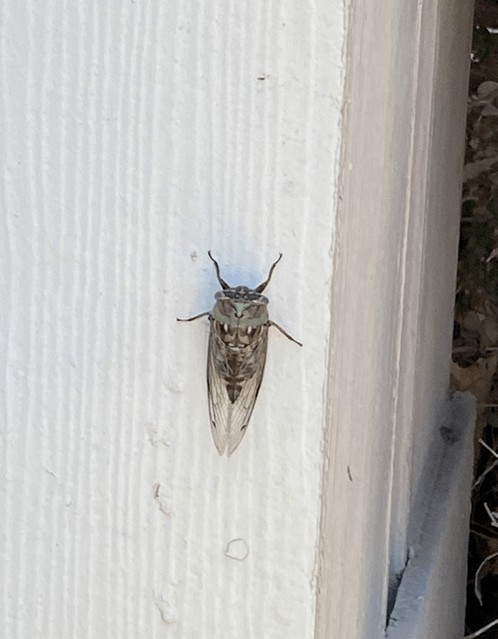

So many times, I have heard someone say, “I just killed the most ugly caterpillar I have ever seen.”

My face turns to horror in my barely contained reaction. After a brief pause to gather my thoughts, I swiftly turn this into an opportunity to educate others.

I ask two questions. One, to describe the caterpillar, and two, what plant or vegetable was it on. Based on those two things, I am usually able to identify the caterpillar. I then proceed to let them know that the ugly caterpillar was going to turn into a beautiful butterfly which in turn is a pollinator that will actually benefit your plant or vegetable. They had no idea!

Sometimes the reaction is, “but they were eating up the leaves.” I then ask if it was a miniscule number of leaves or is it completely devoured. If it’s miniscule and it is a mature plant or vegetable or fruit tree, I say let it be since it won’t be long until it turns into a beautiful butterfly and that mature plant will quickly recover. If it is an immature, young, plant or vegetable, I suggest protecting it with crop covers until it matures and can handle the occasional munching from those caterpillars.

At this point, I remind them of the many benefits the pollinators provide to include bees, wasps, hummingbirds, etc., and how it actually benefits their plants, vegetables or fruit trees by pollination. For most (not all), it is critical that the pollen gets transferred from the male plants to the female plants in order to reproduce. Although some plants, like cedar trees, reproduce by the wind that spreads their pollen, most others rely on pollinators.

The next time you think about killing that “ugly” caterpillar, bee or insect, please look it up to identify whether or not it is a friend or foe. If it a beneficial pollinator, we can always find a way to co-exist.