By Sue Ann Kendall

[I wrote this for my personal blog but accidentally created it on this site, so enjoy my fascination.]

Bear in mind that I have been looking at waveforms most of my adult life, so this stuff interests me. I still edit myself talking a lot (yep, it’s my job), so I know when I’m gasping or clicking from saliva before I even listen. It’s interesting, not that fun.

But it’s only in the past couple of years, since I e had Merlin Bird ID that I’ve been able to identify bird calls by how they look on a spectrogram.

This kind of knowledge is helpful in winter when there are so many sparrows around. Their spectrograms look different. Here’s one I also like.

Songbird recordings look very different. Some are more horizontal lines going up or down with the pitch. Others have a mix of tones, but you can see the melody. These two I got from Merlin, of birds I’ve heard.

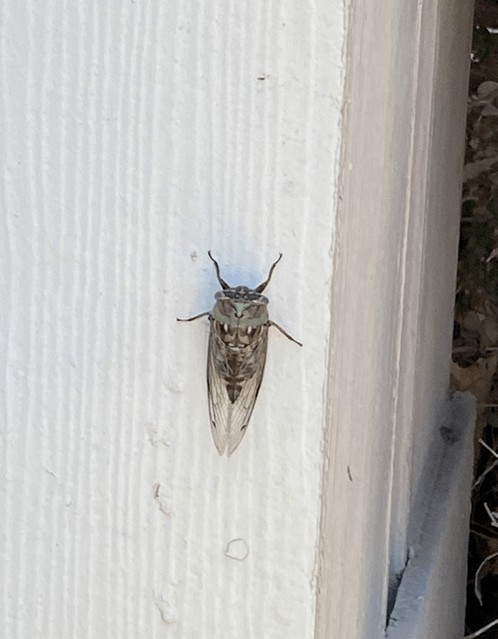

As I’ve been enjoying the sounds birds, there have been other sounds Merlin catches, like loud trucks, airplanes, and wind. And, of course there are insects. I was being deafened by the sounds of late-summer cicadas when I looked down at the waveforms. Wow!

You can practically feel the pulsing by looking at those fascinating shapes. On the other hand, crickets just stick to one note.

So if anyone ever asks me how I know a sound is a cricket versus a cicada, I can turn on Merlin. It may not ID it, but I can now from the shape.

I used to have some frog images but I can’t find them. I’ll be paying attention and when I hear something interesting, I’ll stop the recording, since Merlin doesn’t save recordings over about 20 minutes long, due to storage constraints. My phone would be FULL.